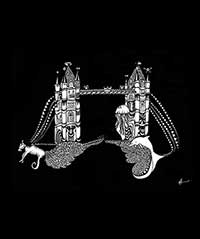

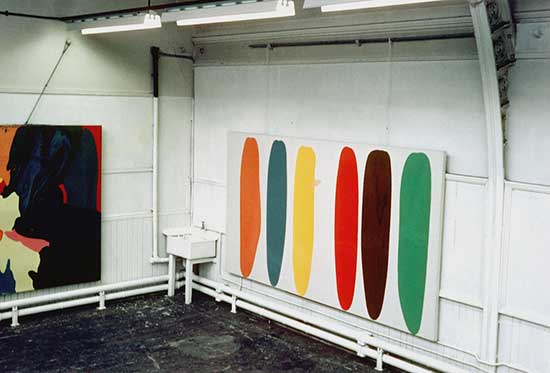

Caveat (1991). Oil on canvas

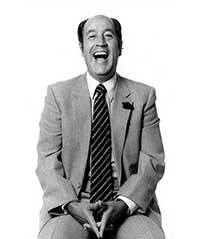

In our last issue I interviewed David Taborn at his studio in Lambeth. Recently we headed out together to several London galleries, and I had the opportunity to take a closer look at his current work.

In March, we visited the White Cube in Bermondsey for ‘A Fortnight of Tears’ by Tracey Emin followed by a brief but rewarding visit to Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery to see the impressive paintings of John Bellany and Alan Davie, ‘Cradle of Magic’. Early in May we headed to the Gagosian Gallery in Mayfair to view ‘Visions of the Self: Rembrandt and Now’.

For those unfamiliar with the career of David Taborn, he paints large abstract canvasses with oils and resins, and makes objects from all sorts of things that look like mechanical beings that might move, function or act.

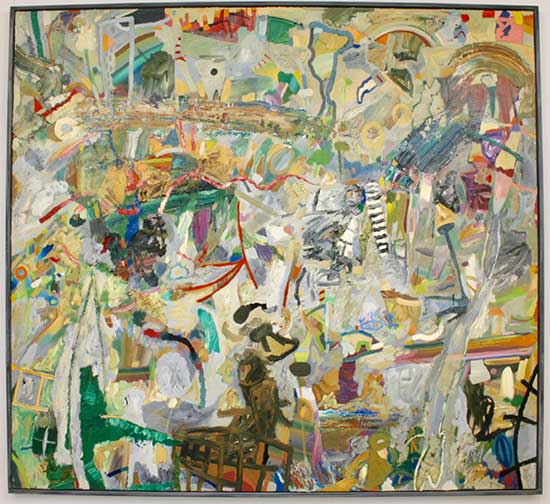

The Crossing (1993). Oil on canvas

In 1964, at the age of 17, Taborn left his birthplace in the Midlands and travelled to Germany, finding work as a postman. The early starts and early finishes gave him the time to draw and paint, and soon enough he had a portfolio of work that took him back to study at Birmingham College of Art. That was followed by the Slade School of Fine Art as a post-graduate. Seven years later he was awarded A Fellowship at Nottingham University, where he made increasingly abstract landscape paintings. Over the decade that followed Taborn became uncomfortable with landscape association as an easy option of abstract expression, and he began taking his paintings and the abstraction even further. In 2003 David Taborn was awarded a three year NESTA Fellowship, followed by the Established Artist Fellowship at UrbanGlass studios in New York, working for the first time with glass and neon.

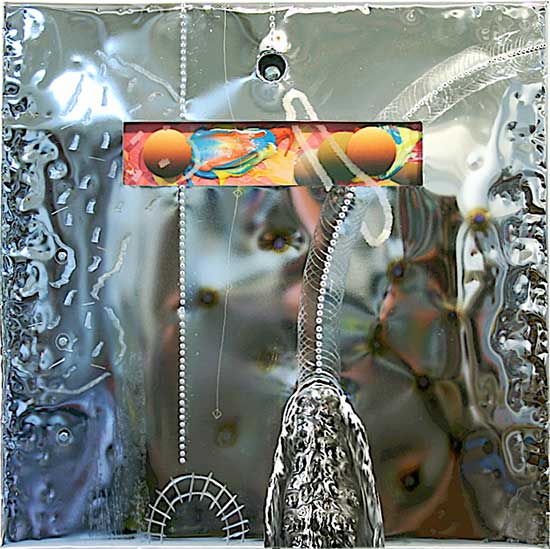

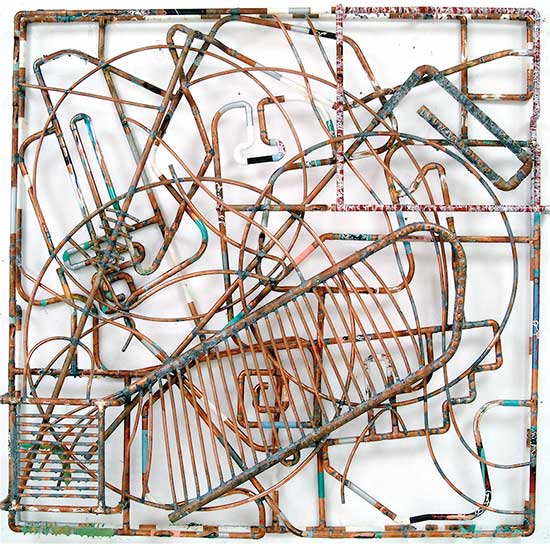

Homunculus – Plate (2006)

Recently Taborn has been experimenting with words and the familiar objects of old books as an alternative material, transfiguring hundreds of them into subversive, irreverent triggers which he called “The Dado Rail of Delusion”. An award from the Gottlieb Foundation last year enabled him to return to painting with fresh momentum and vigour, producing an explosion of new, restless creations that demand to be seen.

Homunculus – Plumb (2005) Treated as a painting, this work is a linear transcription of copper-pipe on a non-existent surface

Our afternoon jaunt to see “A Fortnight of Tears” at the Bermondsey White Cube was fun but Tracey Emin’s work was less so. The first large room was dedicated to an array of huge printed selfie photos taken by Emin in bed, unable to sleep. The next was a collection of minimalist ink drawings inscribed with words of love, loss and grief. Later, David and I stood at the back of a dark curtained room as Emin talked on film. She was emoting about a young tree in a park and an abortion, at which point we snook out. “Time,” as Taborn said, “is of the essence.”

Half an hour after leaving the White Cube we parked up at Newport Street Gallery in Lambeth. Another stunning space, this time decorated with the ominous mood and eerie narratives of John Bellany and Alan Davie’s paintings.

Taborn worked with glass and neon at the UrbanGlass Studios in New York

Damien Hirst opened the Newport Street Gallery in 2015. Back in the early 1990s in London, as Hirst and Tracey Emin were being engaged by Saatchi and staging their first YBA exhibitions, David Taborn crossed paths with them at the Joshua Compston event ‘A Fete Worse Than Death’ in Hoxton. Another young man on the edge of this emerging scene was Compston’s contemporary Jay Jopling, who opened his first White Cube Gallery in the West End and then, two decades later, in Bermondsey.

By 1992, Taborn was 45 and enjoying some success with international sales. Nicholas Alfrey, an academic at Nottingham University, wrote of his work at that time, “It is undeniable that his most successful paintings depended for their effect on a powerful physicality, with densely-layered surfaces. Surfaces are packed with detail, tonal and chromatic organisation is pushed to a point of reckless complexity. At the same time, the paint is applied in a bewildering range of gestures and processes.”

Taborn had once used landscape to explore levels of abstraction, but was abandoning forms like the horizon and planes of land or sky entirely. The paint and expression had become the object and subject itself, where colours float unbounded, ‘space’ is transcended and all marks and layers are simultaneously happening.

When Taborn’s agent and gallerist, Joshua Compston, died in 1996 at the age of just 25, Taborn’s path turned away from the London scene. He collaborated for a short time with composer Nigel Osborne at the Arnolfini Gallery and the Rambert Dance Company before beginning a new approach to objects and abstraction that would ultimately lead him to New York.

When Taborn had completed his NESTA Fellowship and the Established Artist Fellowship in New York he had been taking his painting into entirely new areas. Each fresh creation developed its own visual outcome through the making process. To Taborn these unique ‘characters’ were well-described by the idea of an Homunculus, a small being created by an alchemist. A prolific period had begun in which Taborn produced a large body of four foot by four foot works that pushed his painting techniques and parameters out of the flat pictorial space into three dimensions and multi-material objects.

Art critic and writer for the ArtReview Magazine J.J. Charlesworth, wrote about this set of Taborn’s work: “It’s possible that these objects start from an idea of painting, but they very soon reach the limit of its formal definition, at least in terms of materials; painting seems like a meagre set of options when confronted with Taborn’s cornucopia of material options: just oil on paint? Just on canvas? Just stretched on a wooden stretcher? Is that it?”

Taborn was utilising much more, as Charlesworth went on to describe: “Dripped, mixed coloured resins, running like molten plastic… gouged, routed, ground with angle-grinders, inlaid, cut and re-cut, repainted, layered, masked, spray-painted, drilled, objects set-in and mounted behind glass or encased in clear-resin, pipes constructed and welded – the list of operations Taborn performs on these painting-like objects is dizzying.”

Right from the beginning of Taborn’s career he was experimenting on all fronts. When the Slade agreed to pay his rent for a large railway arch to use as a studio in 1970 he was already setting himself apart, creating a distance between himself and ‘the herd’, between himself and his past techniques.

In May, before we set out to the Gagosian Gallery in Mayfair, Taborn showed me several current works that were taking shape, gathering momentum. Echoes of his past journeys resonate in the pieces which have become simplified, distilled. Painted holes, like time-tunnels lead through to somewhere else, or out behind the canvas. As the eye seeks a pathway, entry points emerge, beams and poles point up through these black holes, targets peep out from behind edges and space opens up unexpectedly. He is clearly enjoying the direct craft of painting again.

‘Visions of the Self: Rembrandt and Now’ at the Gagosian was essentially a celebration of Rembrandt’s ‘Self-Portrait with Two Circles’, a masterpiece painted when the Dutchman was sixty years old. All of the other self-portraits including works by Francis Bacon, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lucian Freud, Pablo Picasso ultimately prepare visitors for Rembrandt’s oil painting which stands majestically in the final room, dwarfing all others with its undeniable mastery, integrity, style and historical weight.

A surprising inclusion in the exhibition that delighted David Taborn as we progressed deeper into the gallery’s heart, was the ‘Portrait de Femme’ completed in 1939 by Dora Maar, the French photographer, painter and poet who famously had a liaison with Picasso between 1936 and 1943. The work is simple, striking and a reduction of the many representations Picasso made of her.

With each passing minute we explored the exhibition, late on that Friday afternoon, visitors steadily arrived and the intimate gallery space began to fill up. We had seen enough and had enjoyed it immensely; it was time to head back south, out of Mayfair, over the river and through congested intersections, under the arches and railway bridges at Vauxhall, all the way back to Taborn’s house, his studio and his next canvasses.

DAVID TABORN

davidtaborn.com