Afternoon

You place your hands in front of me

in answer to my question.

Summer warm, upturned

palms are mute.

I place a cool stone in one

pale grey, white striped and matte,

surface smooth against your lips

as I raise the stone to meet your mouth.

Your eyes flicker,

but remain quiet, watching

A passing car blares then fades music.

Not ours, not here, in silence

stood by the open window

of your Aunt’s spare room, we have only

the sound of sunlight on the carpeted floor.

when I sat down to write this poem, I had only one pre-requisite; that the poem should describe in some way the gloriously sensuous overload that is eating a piece of very ripe fruit. As you can see the fruit is nowhere to be seen in the final draft, or perhaps most recent draft – Stephen Fry, whose poetry I have not actually read, but whose book on poetry I own, says that a poem is ‘never finished, only abandoned’. However, that there is no longer mention of fruit is not a problem. In the writing and the shaping the fruit got chucked and the stone was picked. As the poem slowly emerges from the chrysalis of an initial idea, it changes colour, texture and taste; and in some cases of brutal editing, it grows wings and flies away entirely. And only an image, or an echo of an image remains from its conception.

Looking at the poem now actually, the stone is in fact a piece of fruit, only in another disguise, in another language. My poetry teacher is always reminding us to heed poet Elizabeth Bishop’s advice that a poem should be ‘like a mind thinking’ as opposed to a static thought. I like the image of the poem as an animal because poetry is both familiar and also, to a degree, unknowable.

“I like the image of the poem as an animal because poetry is both familiar and also, to a degree, unknowable

Half the poems I love, if not more, such as T.S Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’, have more channels of meaning than I will ever uncover; I could swim in that poem for years, and still never get to the bottom of it. And I think that one of the reasons that poetry is so powerful and at times so bewildering, is that it doesn’t immediately give itself to you in the same way that straighter prose or non-fiction does.

As an aside, I just want to confirm that I’m not making all these grand claims for this poem (hell no!), as I would not class it in the category of Poetry at all, trained as I am in the art of British self-deprecation. Maybe poetry, with a little ‘p’. But that’s another thing, what is poetry to one person is a pot of piss to another, and absolutely nothing can be done about that! Some people find Gertrude Stein’s ‘modernist’ writing – ‘rose is a rose is a rose is a rose’ – too pretentious, too impenetrable or just too bloody bonkers. Others have lauded her work as challenging a patriarchal system of language in which a rose can only ‘logically’ be ‘a rose’, and not ‘a rose, rose, rose’. I say Gertrude, you are right! a rose IS a ‘rose is a rose is a rose is a rose’!

Do you have a poem to publish or feedback on any of our poems published so far? If so just email us at poetry@therivermagazine.co.uk

-

TWO CLASSICS: The Shipwrights Arms and Simon the Tanner

Taking a look through the doors of our favourite local pubs

Category: Food&Drink -

2013 PROPERTY PRICES Great Expectations

Sales and lettings insights for the year ahead

Category: Property -

THE ART OF GIFTS at bermondsey 167

A concept born of two cultures

Category: Style -

NEVERMIND 'Jam On It', Here's Marmalade

Boutique Marmalade offers their style-savvy customers exactly what they want

Category: Style -

Dedicated Followers OF FASHION

An evening of Champagne and Absolutely Fabulous frocks

Category: Style -

A Surprise Dinner Party WITH GREGG WALLACE

A relaxed atmosphere at the Bermondsey Square Hotel with some great new dishes and a personal touch from Gregg and his team

Category: Food&Drink -

A NATIVITY SCENE Underneath the arches

We talk with Father Michael Cooley at Our Lady of La Salette and St Joseph Church about the history of local traditions

Category: For The Soul -

Art for the people BY THE PEOPLE

Bermondsey artist Austin Emery builds a community sculpture with the local residents of Tyers Estate, SE1

Category: Culture -

OLD FASHIONED Drinking

Tailored cocktails with modern twists

Category: Food&Drink -

A WINTER Hideaway

The sanctuary of the Quarter Bar and Lounge

Category: Food&Drink -

GET READY For a Party!

Introducing a Wicked Wardrobe range by Elly

Category: Style -

Shortwave BY LONG LANE

We meet up with Rob and Dean to view what’s new at the Shortwave cinema on Bermondsey Square

Category: Culture -

A POEM 'like a mind thinking'

The fruit of ideas

Category: For The Soul -

SHAD THAMES in the words of Charles Dickens

Walking through London streets and finding the lost souls that haunt the riverside

Category: Culture -

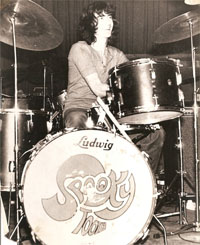

The Baltic JOURNEY

From 1780 until today, we take a look inside the changing space of 74 Blackfriars Road

Category: Food&Drink